Since its inception in 1990, the H-1B guestworker program that allows employers to bring in high-skilled foreign workers on six-year visas has been steeped in controversy.

The program has been the subject of dozens of congressional hearings, including one just last week in which I participated, frequent op-eds from pundits and technology moguls, exposés and legislative changes. Critics accuse it of depressing wages and outsourcing American jobs, while advocates call it an essential source of the best and brightest talent.

But this year marks the first time it has risen up to the stage of a presidential campaign. The leading candidates in both parties have staked clear and competing positions about how to change the program, either greatly expanding it (Marco Rubio, Hillary Clinton) or tightening the eligibility criteria and requiring the recruitment of American workers first (Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Bernie Sanders).

But what exactly is the H-1B visa and how does it work? And how would different reforms and changes improve the program?

Since there is much mythology about the program, let’s take a step back and look at what it is intended to achieve to dispel the myths and the confusion.

I have been exploring issues surrounding high-skill immigration and offshoring for more than 15 years and believe a better understanding of the program will help us assess the candidates’ positions. And my view is that the program is being widely abused by companies and needs to be reformed to ensure it is meeting its intent while providing adequate protection to American and foreign workers alike.

H-1Bs were meant for specialized workers but often are used for jobs that can easily be filled by Americans.

Exasperated accountant via www.shutterstock.com

What’s so ‘special’ about it?

The program has its roots in the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act as a way to bring in foreign workers “to perform temporary service of an exceptional nature requiring such merit and ability.”

The 1990 Immigration Act formally created the H-1B visa and made two significant changes to the original program: 1) allowing “dual-intent” so that H-1B workers could pursue permanent residency and 2) setting an annual cap of 65,000 people.

The statutory cap has changed multiple times over the years, rising as high as 195,000 at the peak of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s and settling at 85,000 since 2005. In 2000, Congress made certain employers such as universities and research institutions exempt from the cap, meaning in reality about 120,000 new H-1B workers are approved each year.

The “dual intent” provision made the H-1B an important conduit for skilled workers to permanently immigrate, while the program’s intent remained to fill skills gaps in the labor market and provide a way to bring in workers in occupations for which Americans were hard to find.

‘Best and brightest’

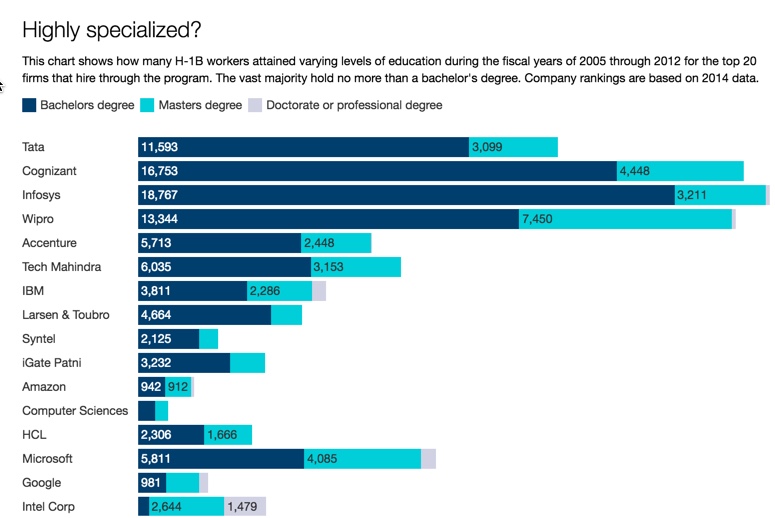

The main problem with the H-1B currently is that it’s focused on “specialty occupations,” but there really isn’t anything special about most of the H-1B workers being hired. Rather than filling specialized skills gaps in the U.S. labor market, most H-1B workers have no more than ordinary skills, ones that are abundantly available from the available American talent pool.

While industry advocates such as Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Michael Bloomberg and the lobbying groups they support argue that H-1Bs help the U.S. lure the “best and brightest” from abroad, the reality is that the educational threshold for an H-1B is only a bachelor’s degree. And in fact, the majority of technology industry H-1Bs hold no more than that.

In practice, the program can – and is – used to fill any occupation that typically requires a simple undergraduate degree, such as journalism, accounting and marketing.

H-1B workers can be brought in even in occupations where there’s an abundance of American workers, such as the legal and sales professions. Employers need not show that there are shortages of U.S. workers, do not need to seek local hires first and can even replace Americans with H-1Bs.

Further, the intent is that H-1Bs be paid market wages, but the reality is that the “prevailing wage” rules for H-1Bs are flimsy and it’s extraordinarily easy to pay an H-1B worker much less than an American worker.

Disney, which recently celebrated the 50th anniversary of Disneyland, replaced American workers with foreign ones using the H-1B visa.

Reuters

Replacing American jobs

Those advocating for reform of the program, like myself, have argued that it has mostly been used to replace, and substitute, Americans with cheaper labor, which as I’ve shown is extraordinarily easy and profitable.

And that’s why, in a campaign season that has highlighted immigration and middle-class pain in the U.S., the H-1B has received such unusual prominence.

Should there be any doubt that employers have a self-interest in finding the cheapest workers available, one need only to look at the wage-fixing scandal in which the CEOs of the two most valuable and profitable firms in the world – Apple and Google – conspired to keep their workers from getting fair wages.

Last year, Southern California Edison, the state’s largest utility, replaced 400 American IT professionals with H-1B workers from India and then required those getting fired to train their replacements.

Why did Edison do it? The reason was simple: the H-1B workers were cheaper. The cost savings were US$40,000 to $50,000 per worker, or 40 percent to 50 percent less than an American. The Department of Labor recently completed its investigation of Edison and its contractors and found no violation of H-1B rules. In other words, the department affirmed that it is legal to pay H-1B workers substantially less than Americans and to even replace Americans with H-1Bs.

Edison’s case was not unique. Over the past year, Disney, The Fossil Group, New York Life, Abbott Labs, Catalina Marketing and Toys R Us have all replaced – or are in the process of replacing – American workers with H-1Bs. The business model of using the H-1B program to facilitate permanent offshoring is a well-known and widespread practice. The top 10 H-1B employers are all offshore outsourcing firms that use the program to facilitate shipping American jobs to low-cost countries such as India.

If a company like Disney, which received great scrutiny in a series of front-page New York Times articles, will exploit the H-1B program while under the spotlight, what company wouldn’t?

Another criticism of the H-1B program is that it upends the normal employer-employee power relationship. Since it’s intended as a nonimmigrant guestworker visa – most H-1Bs are not sponsored for permanent residence – it invites abuse and exploitation. These conditions – lower wages, offshoring of the jobs and an imbalance in the employer-employee relationship – lead to depressed wages and working conditions for all American workers in these fields.

The H-1B visa has been a big part of the debate over immigration reform.

Reuters

The candidates and the H-1B

So where do the presidential candidates stand?

Republican frontrunner Trump is targeting the wage issue directly, calling for an increase in the minimum salaries paid to H-1B workers in order to prevent the program from being used for cheaper labor. He would also require that employers recruit American workers before they could hire someone under an H-1B visa.

These are both steps in the right direction, though details remain lacking. It’s worth noting that Trump has been attacked by his rivals for hiring large numbers of H-2B unskilled seasonal guestworkers for his resorts.

Senator Rubio is an original cosponsor of the so-called I-Squared Act, which would more than triple the number of H-1Bs issued.

When the topic arose in one of the first Republican debates, he claimed the act would also help curb the program’s abuses by requiring employees to seek Americans first and higher wages for H-1Bs – which both The New York Times and I have refuted.

Like Trump, Senator Cruz has expressed concern about the program. He has proposed an even bolder reform plan that involves a 180-day moratorium to investigate program abuse, lifting minimum wage and educational requirements and making it harder to use the program if a company is laying off Americans. That’s a significant reversal from his earlier position on the H-1B. During the 2013 debate, he introduced a failed amendment to the immigration reform bill that would have increased the H-1B cap five-fold, with no additional protections.

On the Democratic side, the H-1B visa – like immigration generally – hasn’t been as hot a topic, though the two contenders are on opposite sides of the issue.

Former Secretary of State Clinton has long advocated increasing the H-1B visa cap, yet has been silent about whether she would clean up any abuse. Senator Sanders, on the other hand, has advocated reform of the program and has cosponsored bipartisan legislation in prior Congresses crafted by long-time reform advocates Senators Charles Grassley and Dick Durbin.

These bills would raise minimum-wage levels, give American workers a first and legitimate shot at jobs before they are offered to H-1Bs, prevent a Disney-like replacement of American workers and institute random audits to ensure compliance (the current compliance system relies solely on whistle-blowers).

Where reform begins

As someone who has researched this program for more than 15 years, and advocated for its reform, I’m glad to see that the issue is finally getting some recognition at the highest levels of politics.

To me and many others, the solutions are obvious, and variations of them are already available to lawmakers in three recent bills introduced in the Senate. The majority of H-1B workers are being hired because they are cheaper than Americans. We believe that the solution is to raise wages – and raise them substantially – and ensure that American workers have a first and legitimate opportunity for these jobs.

The H-1B program is an important program that serves as a bridge to permanent immigration for talented foreign workers. It should be used to recruit truly specialized workers from abroad when the labor conditions are tight and a qualified American can’t be found. But no American worker should ever be displaced by an H-1B worker – that was never the program’s intent – and this practice should be ended.

Ron Hira, Associate Professor of Political Science, Howard University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.