Revendra

The case for reservations (affirmative action) in India stems from compensation for historical wrongs, social and economic discrimination and disparities. To address these issues, the reservations were implemented initially for Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Scheduled Castes (SCs), followed by the Other Backward Castes (OBCs). Reservations were limited to jobs in public sector, admissions in the higher educational institutions, and some constituencies for political representation.

The effect of reservations on political, social and economic upward mobility of these deserving communities is still under debate and investigation .In case of SCs and STs, the government ensured their recruitment and minimised the percentage of vacancies, a study observed that the reservations reduced only a small drop in the poverty among the Scheduled Tribes, and has no affect on the Scheduled Castes. In case of OBCs, only 7% of the reserved 27% jobs were filled.

Kapu/Balija castes (including all the sub-castes), constitute 27% of the population in Andhra Pradesh, and with 238 associations across the state, they form a community extremely difficult to manage for any political party. Undoubtedly, they played a key in 2014 elections that helped Chandrababu Naidu to return to power.

Naidu, known as a reformist, is not naive to commit political suicide by ditching the demands of this community. Naidu constituted Justice Manjunath Commission to fulfil the poll promises made to the Backward communities in Andhra Pradesh, and also a Kapu Welfare and Development Corporation was set up to serve the marginalised communities of the castes — Kapu, Balija, Telaga and Ontari.

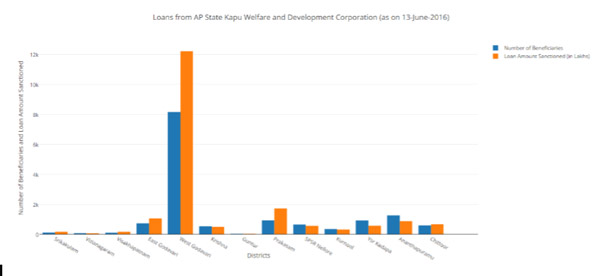

Since it’s inception AP State Kapu Welfare and Development Corporation has sanctioned subsidised loans of ₹187.9 crores to 14,355 members of these communities (as on 13-June-2016), with most of the beneficiaries hailing from West Godavari district.

the castes — Kapu, Balija, Telaga and Ontari.

Andhra Pradesh is one of the states with 66.66% (the highest) of reservation in the country. Technically, it is impossible to provide an extra percentage of new reservations to any castes, and adding them to the existing categories will pose resistance from the other communities.

[table id=40 /]

Break-up of the Castes and Reservations in Andhra Pradesh

The Justice Manjunath Commission constituted to address the socio-economic issues of backward classes in Andhra Pradesh had administrative hiccups initially but now faces severe methodological and strict timeline challenges. The Commission is not considering Socio-Economic Caste Census (2011), and has to tour across the State, make an assessment that is scientifically acceptable. The challenges are further exacerbated by the cap set by the High Court on the percentage of BC reservations. In February 2016, the Chief Minister has urged the Commission to submit the report before the 9-month deadline, and in March 2016, Governor E.L. Narasimhan, during his speech at AP Assembly, assured that Justice Manjunath Commission may be out in 8 months i.e., November 2016. The current agitation by Mudragada Padmanabham exerts more pressure on the Commission to submit the report much earlier, and if happens will certainly make the report vulnerable to not only methodological scrutiny but also political criticism, and likely rejection from all the communities.

The methodological issues stem from “how to identify an individual from the Kapu communities as a deserving person for reservations?”. If the economic backwardness is the criteria, then the AP State Kapu Welfare and Development Corporation can make provisions to provide financial assistance to them, ruling out the inclusion in the “Backward Classes” reservation category. If the social backwardness is considered, the individuals from wealthy families (otherwise, the creamy layers) will enjoy the fruits of reservation at the cost of other disadvantaged individuals. Either of these decisions has severe political repercussions, and will not die anytime soon.

History always has lessons to learn from. The first Commission on Backward Classes chaired by Kaka Kalelkar faced issues with lack of reliable data, and provided the recommendations based on the statistics available from the various Governments and the previous census reports, and the general impressions of Government officers, leaders of public opinion and social workers. “In certain cases, the Commission was compelled to take a decision on “the strength of the name of the community only, on the principle of giving the benefit of the doubt”. The Kalelkar report when tabled in the Parliament in 1956, the Government discouraged the use of caste, and stated that caste was “the greatest hindrance in the way of our progress toward an egalitarian society” and warned that the “recognition of specified castes as backward may serve to maintain and perpetuate the existing distinctions on the basis of caste”. The criteria evolved by the Commission, when they were not exclusively dependent on caste, were “obviously vague”.

Hope the Justice Manjunath Commission took the lessons from the history, remains untouched by the political pressures, follows the scientific methods, and comes up with rational recommendations that will not exacerbate the existing political divisions and achieves the egalitarian aspirations of all the castes in Andhra Pradesh.